A Brief History of Merino Wool

Way back in the depths of time, not hidden but certainly unclear, are the origins of the sheep breed we know as Merino. We can easily find information on its recent history, but delving back before the Spanish developed and refined the breed into the one we are familiar with today, reveals that there can be conflicts in information and shows a potentially broad origin indicated in the development of this prized sheep.

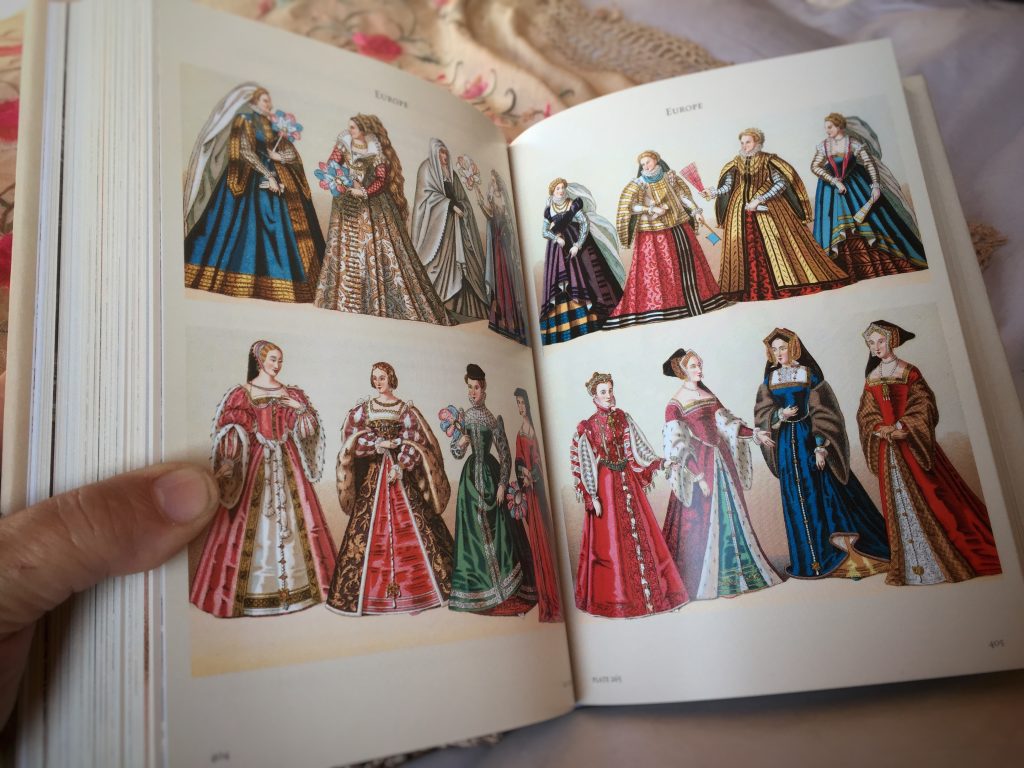

What we do know is that it is thought the Merino breed was first introduced into Spain in about the 12th century, probably by a north African Berber tribe named the Marinids. There are indications that the Spanish further developed this north african sheep by breeding with some other introduced English breeds, to develop a wonderful wool-producing sheep with a fleece prized for its softness and fineness. From this point on, and for another 400 years, the Spanish dominated the wool market with their ‘special’ sheep, and they protected this jealously, maintaining a monopoly on the breed with a strict policy of not sharing the bloodlines outside of the country. And not without reason! The fabrics created from the Spanish Merinos were highly prized, and wearing clothing made from the beautiful fabric it produced was considered to be a ‘mark of wealth’. Furthermore, Merino flocks were generally held by nobility or the church, all with vested interests in maintaining their exclusivity, as well as the power to do so.

How did they enforce their monopoly of this sheep breed in Spain? Exporting on penalty of death! It seems a drastic measure, but it appears to have worked, the Spanish were known for their Merino wool and didn’t just dominate the market for it but held a monopoly. Perhaps it was fairly unique that this was a breed specifically farmed for fleece, in fact being a very lean, slow maturing sheep, it was not much valued for its meat, while in the rest of Europe, sheep were primarily meat animals, at best farmed for a compromise between suitable meat production and a useable fleece. I am sure there were other fibre sheep at the time producing soft fine fleece for yarn, but perhaps not with the consistency or fineness of the Spanish Merino, which of course also carried the elite name and reputation.

It seems really quite remarkable that they maintained this monopoly for as long as four centuries! But despite the Spanish efforts to keep their Merino exclusive, it was probably inevitable that at some time the breed would be ‘officially’ shared and spread into other parts of the world. It is thought this first happened in 1765, when King Carlos III of Spain gifted a flock of his Merino sheep to the German Elector of Saxony. However even before this time, and perhaps because of a falling market for wool throughout Europe, there had been some allowances made for the exportation of Merinos (in small numbers) from Spain, and local sheep were then bred with them to create the foundation of Merino flocks in other countries. However it seems to be a general mythology that the gifting by the Spanish King to the Germans was the trigger point to the spread of the Merino breed throughout Europe.

There are now four main ‘strains’ of Merino recognised, aside from the ‘original’ Spanish breed. The first is the Saxony Merino, derived from the Negrette strain which was marked for being large sheep with a short staple length fibre. Then there is the Silesian or German Merino, which is said to be a mix of Negrette, Escurial (known for dense, crispy wool), and Infantando (originally from the flock of the Duke of Infantando). The French Merino, or Rambouillet is another known strain of merino, and it is thought to have some long wool heritage included in the breeding. Lastly is the Vermont and Delaine strains, bred in the United States. Each of these strains have somewhat different characteristics, such as the extra crimp in the Saxony strain and the bounciness of the French Rambouillet, but all these variations share a number of common characteristics that make them recognisable as ‘Merino’

So what is it that makes Merino distinct from other fibres? One of the first and most obvious characteristics noticeable in any raw (unwashed) Merino fleece is its high lanolin content. Merino is what is known as a ‘greasy’ fleece and for this reason requires a slightly different washing method than other fleeces with lower wool wax content.

Merino fleece is also highly prized for the fineness of the fibres, as low as 13.5 micron, and most usually in the lovely next to skin softness of between 15-22 micron range.

It is also known for its wonderful crimp, very fine micron means very fine crimp that results in a very fine yarn with lots of bounce and elasticity. It is possible to create very light and airy lace pieces with yarn spun from fine quality merino, think about the famous ‘wedding ring shawls’ that will literally fold down to fit through a wedding ring! Light and bouncy, Merino is ideal for this kind of knitting.

One of the foremost Merino lace spinners in the World is New Zealand’s own Margaret Stove. I highly recommend her books and DVD’s for detailed information about washing and spinning Merino for lace, she has been a true pioneer in this field, developing her own methods through experimentation and experience. You can find her work online at the Interweave store HERE – I highly recommend this video! Margarets methods will help you achieve stunningly bright clean fiber and laceweight yarn full of elasticity and bounce.

There is nothing more satisfying than taking this amazing fibre from raw to yarn, at each step it is a pleasure to work with, and knowing the history of this breed tells us the stories of those who have come before us in developing and using this wonderful fibre 🙂

Further Reading

Further Reading

http://www.simplymerino.com/The-History-of-Merino-Wool_b_7.html

Wonderful post, full of information. I didn’t realize that merino sheep originated in Spain. I always thought they came from Australia or New Zealand. So, I learned two things today….third little fact, and the fact that Ramboullet were merinos. Thanks for the education!

Thank you for this, Suzy! I didn’t know about the official guarding of the breed for such a long period.

At some point in the 1500s the Spanish brought animals to the Gulf Coast of Florida and Louisiana, including sheep which are believed to have been “pre-Merino” stock. These sheep quickly changed and evolved to adapt to the hot, humid, and wet conditions. They became smaller, lost the wool from their legs and bellies, developed resistance to parasites, and feet that were less susceptible to rot.

Other breeds were combined, and eventually this sheep came to be known as the Gulf Coast Native.

We also have Florida Cracker sheep, another tough meat breed believed to have descended from Churro sheep also brought by the Spanish.

I am fascinated with these particular breeds because I live in the area and have hand processed and spun plenty of GCN, which can be so lovely. I am awaiting delivery of a Florida Cracker fleece at the moment.

Warm wishes from Sunny Southwest Floriday!

Amy G

Nice informative post! Thanks!

Its a fine history thank you .I dont know much about the original Kiwi merino breeding but my pet peeve is the somewhat overlooking of the powerful role women had in Australia`s merino history. They were the brains behind many of our famous lines but it was to their husbands went the glory.

In Tasmania a little step of recognition has happened. You may like to take a look at Eliza my hero.

http://monumentaustralia.org.au/themes/people/industry/display/99815-eliza-forlong-and-ram